This is Part 2 of a three-part narrative. Read Part 1 here.

At 8 years old, Salemu Alimasi had already spent 18 months in a refugee camp far from his home in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In 1998, he was thrilled to be back in Uvira with his parents and siblings.

However, the First Congo War had barely ended when the Second Congo War began (1998 – 2003). The DRC, then led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila and his son Joseph, had allied with Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe to defend the country against soldiers and rebels backed by Rwanda and Uganda. Even when the war officially ended, violence continued throughout the Great Lakes region.

Salemu recalled this part of his childhood:

Seeing dead bodies became regular. There were funerals every day as families were killed while sleeping. Kidnappings and rape were used as war weapons. All we heard was the sound of gunfire… We waited for death to knock on our door.

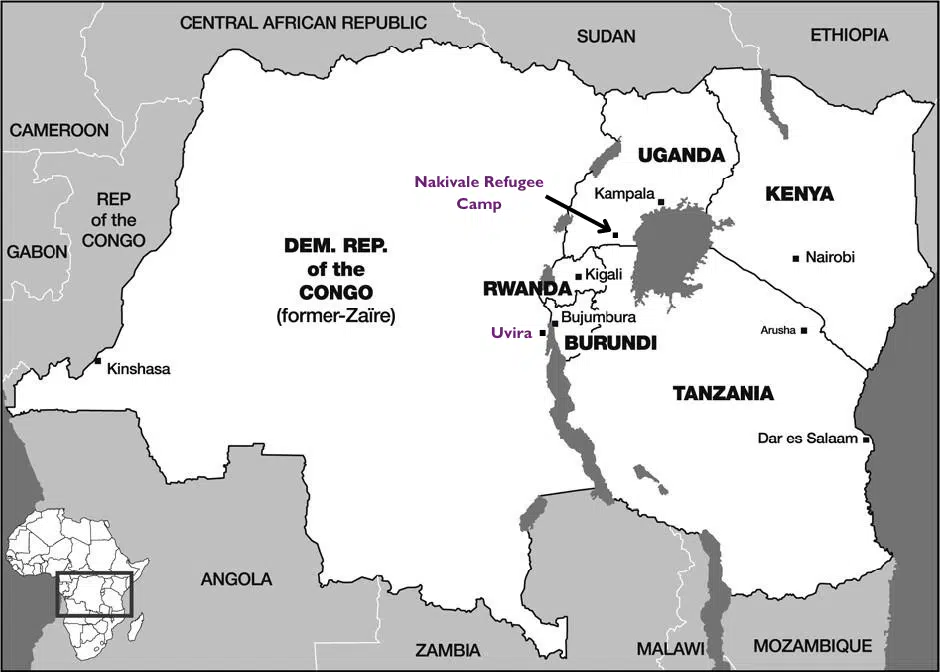

In this context, Salemu’s father had become a pastor and human rights activist, known for his preaching in churches and on the radio. His outspokenness – encouraging forgiveness of past violence as a pathway to peace – earned him enemies. After several of his closest associates including Pascal Kabungulu, founder of the organization known as Héritiers de la Justice, were killed, he decided in 2008 that the family needed to flee. This time, the Alimasis traveled northeast, through Burundi and Rwanda, until they reached a refugee camp in Nakivale, Uganda.

Map of the Great Lakes Region, by International Committee of the Red Cross

Nakivale Refugee Camp, first established in 1958, was by 2008 home to over 100,000 people, including many Congolese. The Alimasis soon found themselves assigned to one of the camp’s “villages,” groupings of 800-1,000 people who shared a common language. However, like all new arrivals, they were expected to construct their own shelter – by first fabricating mud bricks. As Salemu explained,

The camp provided a monthly ration: a set amount of dried corn, beans, salt, and flour for each person. To eat more than that, you had to plant a garden. If you wanted anything else, you had to work for it. I joined other young men, and we worked in groups: digging toilets or making mud bricks.

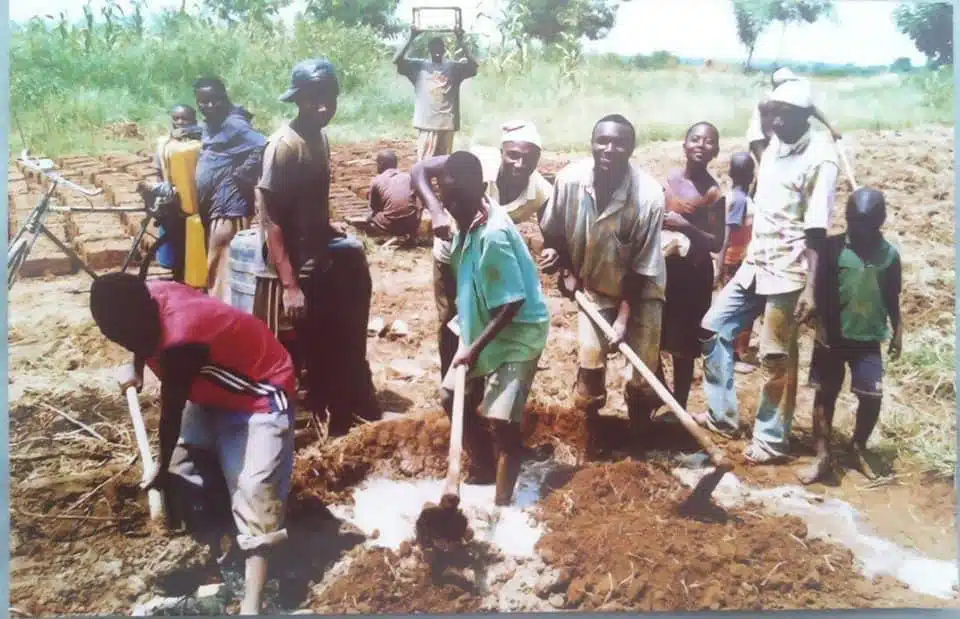

In one of his few surviving photos from Nakivale, Salemu identified himself working with other youth to make mud bricks (seen drying in the sun in the background). Working together for days and weeks, they built simple shelters.

In addition to building a place to live, the Alimasis began creating other resources necessary to their well-being for as long as they had to live at Nakivale. Refusing to simply dwell in misery, they worked to foster a sense of community and hope, starting with the village’s church. As Salemu recalled,

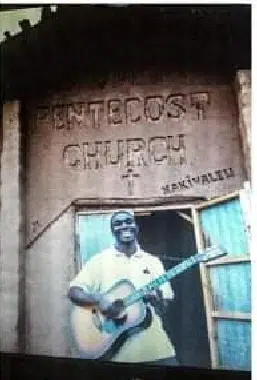

I joined the choir in the church. In time, the choir increased to 45 people, and that brought more traffic to the church. Then we created a theatre group for youth. As interest in the community grew, my father decided to create a new church: Sayuni Pentecostal Church [“Sayuni” means “Zion” in Swahili]. We made so many bricks! After about 4 months, we had enough to start constructing a new building.

Salemu played and taught guitar to youth at the Sayuni Pentecostal Church, whose building (above) slowly took shape in 2009-2011 and remains a vibrant part of the camp today (its current structure, below).

Salemu directed young musicians and singers at Nakivale Refugee Camp.

While the Alimasis worked to improve conditions at Nakivale, they also looked for longer-term solutions. At appointments with UNHCR staff, Salemu’s father made it clear that given the threats to his life and continued violence across the region, the family wanted to be considered for resettlement to a third country. The process required time and patience.

Finally, in September 2011, they learned that all seventeen members of their family group at Nakivale would be resettled through Catholic Charities in Houston, Texas. They had no connections in the U.S., but Houston was a diverse city where they believed they could live in safety and eventually feel at home.

Salemu and his family received this news with “mixed emotions.” As he explained,

Just a few days before we had to leave, we were inaugurating the new church building. I had taught all these young people to sing and play the guitar, and they were serving God with zeal. At the same time, we knew we couldn’t stay at the camp. We said, ‘God, we have done what you asked us to do.’

And so, with their confidence in God’s faithfulness renewed by their success in building community at Nakivale, the Alimasis packed up their few belongings and left for the United States.

The next part of Salemu’s journey will be continued in a subsequent post.