Editor’s Note: This blog post was written by Michael Fitzpatrick, originally featured on Journey With Jesus: A Weekly Webzine for the Global Church Since 2004 , posted originally on October 3, 2021. All opinions and views are Michael Fitzpatrick’s and do not represent EMM. We respect and lift up a wide range of experiences and opinions that inform the welcoming movement.

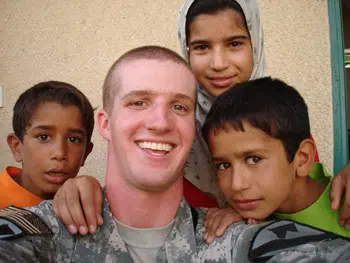

Michael Fitzpatrick is a parishioner at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Palo Alto, CA. After growing up in the rural northwest, he served over five years in the U. S. Army as a Chaplain’s Assistant, including two deployments to Iraq. After completing his military service, Michael has done graduate work in literature and philosophy. He is now finishing his PhD at Stanford University.

–

One morning in October, 2007, I joined my cavalry scout unit for a patrol mission along the Tigris River northeast of Baghdad, Iraq. The patrol was standard for this particular area, although that day I was helping out with a special assignment: the delivery of school supplies to a local Iraqi primary school that had recently been able to resume thanks to our efforts securing the region. The morning light was just beginning to pierce through the treetops. In contrast to the dusty barrenness of much of our assigned area of operations, the area alongside the Tigris is often lush and fecund, with bountiful trees burgeoning with pods of fruit and dense leaves.

As we rounded a corner, my gaze was met with the most awesome sight: young girls in blue school uniforms, roughly ages 6 to 10, were walking two-by-two holding hands alongside the road to school. The transcendent beauty of that scene as we slowly idled by them in our HMMWV pierced our whole truck. We sat in breathless silence as hardened combat troops passed what we could only later describe as the purest embodiment of love and innocence any of us had ever seen. After they disappeared from sight, the other sergeant in the truck softly broke the silence—“That is why we fight.”

Young Iraqi school girls in uniform able to safely attend primary school.

Rarely did I experience war produce a truth in my 27 months in Iraq between 2004-2008, but at that moment, a truth was uncovered. We got up every morning and risked our lives so that beautiful Iraqi school girls could safely hold hands on their way to school. As someone who had been through the hell of picking up the exploded remains of children in the wake of a car bomb explosion, the scene of children secure and flourishing truly is heaven. I wish I had been self-aware enough in that moment to take a photograph, but I have included here a photo I took of two of the girls later that day in front of their school.

We were sent to Iraq to disrupt Saddam Hussein’s production of weapons of mass destruction, a farce we quickly exposed. When we deployed back to the States, my fellow country people praised us for “fighting for our country,” and in regards to our fallen comrades they said, “They gave their lives to keep us free.” But no American freedom was at stake. We weren’t fighting for our country, or to keep our country free. As a soldier, when you discover that you’ve been deployed under false pretenses and shady motives, you can no longer look to the symbols or rhetoric of your nation to give meaning to the awful violence you endure and inflict. Sometimes meaninglessness consumes, as the nihilism of the Vietnam-era war stories testify. For many of us serving in Operation Iraqi Freedom, we staved off nihilism by finding meaning in a different place: serving the Iraqi people through helping them build a better world, whatever the objectives of the politicians back home.

It has been a struggle as a war veteran to watch the fallout of the U. S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. Many Afghanistan veterans have stories like mine. After the death of Osama Bin Laden, those who deployed to Afghanistan felt a responsibility to ensure that the freedoms of the people, especially the women, would become a lasting reality for the local tribal communities who could not remember a time before civil war and oppression. The hope of self-determination is a wonderful gift. It gives a soldier’s life meaning, that our trauma and our PTSD and the blood on our hands and our dead friends weren’t all for naught.

Sharbat Gula, the Afghan girl from the June 1985 National Geographic cover, in mosaic.

So I struggle when President Biden justifies the withdrawal on the grounds that, “Look, let’s put this thing in perspective. What interest do we have in Afghanistan at this point, with al Qaeda gone? We went to Afghanistan for the express purpose of getting rid of al Qaeda in Afghanistan as well as getting Osama bin Laden. And we did.”

Maybe we did, although Gen. Milley’s testimony before Congress suggests a continued presence of al Qaeda in Afghanistan with potential for growth. I’m more interested in the almost exclusive justification of the withdrawal in terms of national interests. The American interest in the country was to fight the war on terror; we did, now let’s go home. But surely it cannot be that simple. Leaving a power vacuum guarantees that those with impure motives will fill it. Do we not have a responsibility to those peoples, to the Pashtuni people, the Tajik people, the Hazara people, the Uzbek people, the Aimaq people, or the other peoples who have now fallen back under Taliban control?

I am not a policy expert, nor do I have a full understanding of all the geopolitical realities in the Middle East. I do have serious doubts that President Biden’s predecessor had any business negotiating a withdrawal with the Taliban and not the legitimate government of that nation, which Gen. Milley has now testified severely weakened the ability of the Afghani military to resist a Taliban takeover. But more than anything I want to affirm, as a war veteran, that when my nation engages in misguided foreign wars, the right thing to do is set aside the interests of the most powerful and affluent nation on earth and ask, what do these people need? Really listen to the voices of those who live in the land. As a soldier, if my presence is what stands between the oppressed and their oppressor, I do not want to leave until the threat of the oppressor has been eliminated. The just war, if there is such a thing, is the war making a necessary defense, not only ours but the defense of the vulnerable, and we ought not abandon the vulnerable until peace is something they can hope for.

Nor is it just my lens as a war veteran that leads me to this conviction. I am foremost a Christian. As people were watching news streams out of Afghanistan during the withdrawal, many were thinking of these geopolitical events simply as a political calculation, in terms of national interests, time in country, and probability of success. Even some coming from Christian perspectives seemed to reduce the war in Afghanistan to geopolitical realities, “In the view of Aquinas, the war must be waged by a lawful government, for a just cause due to a wrong done by those attacked… The [Afghanistan] war became a proxy battle, with the Taliban having not inflected [sic] any injury on our country other than fighting against our establishment of a different government in their country.” (link).

The author with some Iraqi children at a clinic receiving free medical care.

Since the Taliban didn’t attack our home soil, it does not matter to us what the Taliban’s mission is with respect to the free peoples of Afghanistan and their home soil (nor that they are not a lawful government in their attacks on us or the other Afghani peoples). Well, as a follower of Christ, I believe God’s heart pushes us to think of not only our own national interests (whether or not we’ve been wronged), but of what our neighbors need. Karl Barth famously said that the Christian life is surrounded by both “near and distant neighbours” (Church Dogmatics, III.4, section 54.3). We often hear the story of the Good Samaritan and think piously that we need to treat those in our community as Jesus has commanded. But who is “our community”? Not only those people in our neighborhood, but also those on the other side of the city. Not only those in our state or province, but those on the other side of the country. Not only those in our time zone or hemisphere, but also those on the other side of the world. Our distant neighbors are still neighbors. “Called to obedience [to Christ] among near neighbours,” Barth writes, “in the same obedience [a person] is turned to those who are distant.”

It’s not enough that the Taliban never attacked the United States on our home soil. For they attacked their near neighbors, even their own kinsfolk, on their soil. Surely if there is any justification for maintaining the most powerful and technologically advanced military in the history of humanity, it is that we can help the vulnerable in their time of need. For that is a mission far more worthy than advancing American interests abroad. Much of our failure in Afghanistan is due to our persistent inability as a nation to separate these two aims.

I’m reminded once more of the awesome words of the Syrophoenician woman when she begged Jesus to heal her daughter in Mark 7.24–30. After telling her that the children’s bread should not be given to the dogs, she told the Christ that even dogs eat the children’s crumbs under the table. We possess the most powerful military in the world. Perhaps our distant neighbors in Afghanistan just wanted a few more crumbs from our table.

Michael Fitzpatrick welcomes comments and questions via [email protected]

To help in the welcoming of our newest, distant neighbors, please donate to our Afghan Allies Fund.